Who's Using GPM Data

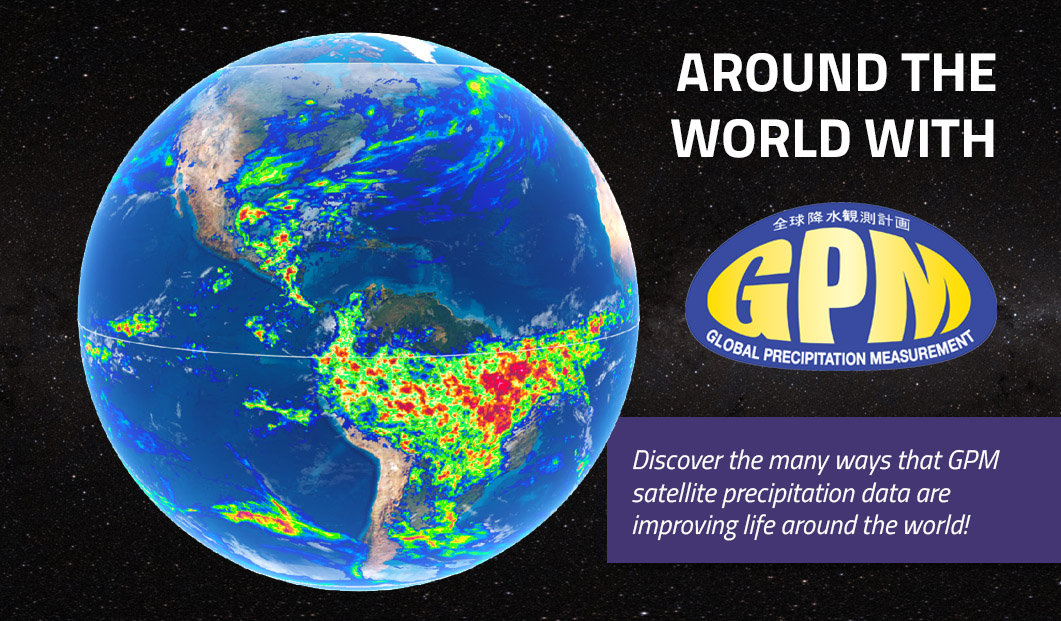

This collection of resources explores some of the people using GPM and other NASA Earth data, and how they help improve life around the world.

- Around the World with GPM

- Min-jeong Kim, NASA Climate Research Scientist

- Greg Elsaesser, NASA Research Scientist

- Sarah Davidson, Data Curator at Movebank

- Liz Saccoccia, Research Analyst at World Resources Institute

- Faisal Hossain, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

- Iker Llabres, Micro-insurance Actuary

- Predicting Earth's Climate with NASA Data

- How NASA Data Helped During the 2020 Hurricane Season

- Using GPM and Other NASA Earth Data to Understand Vector-borne Disease

- Helping Predict, Monitor, and Respond to Malaria

- Helping Predict Outbreaks of Cholera

- Helping Track Zebra Migration

Around the World with GPM

Min-jeong Kim, NASA Climate Research Scientist

Greg Elsaesser, NASA Research Scientist

Sarah Davidson, Data Curator at Movebank

Liz Saccoccia, Research Analyst at World Resources Institute

Faisal Hossain, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Hossain uses a plethora of NASA Earth observation data ranging from precipitation to water levels, land cover, soil moisture, and land/water temperature to take a pulse of the earth we live in and how it is changing. These data are used in many decision support systems to tell us what might be the future state, for example, of flooding, or how much food a region may expect to grow, or even how much drinking water may be available in a region. Predicting the future helps us make decisions on how to prepare, whether that is for the next day, next week, next month / season or even next year. Hossain also works with a project that uses precipitation data and weather forecast data to tell farmers when and how much to irrigate and even inform them if they can save water by not irrigating. This results in a lot of saving of water and increased food production. Hossain also uses NASA data to monitor how warm or cold river waters are below a dam to understand if that dam is causing damage to the eco system.

Resources

- Article / Video: Satellite Data Empowers Farmers

- Written interview with Faisal Hossain

- Lesson Plan: Water for Wheaties

Iker Llabres, Micro-insurance Actuary

Llabres designs and evaluates index insurance products for low-income and vulnerable populations. To achieve this, he plans and executes methodological analyses that aims to improve the quality of index insurance products. Llabres needs to explain the products that he has designed, as well as their functioning, to insurance supervisors, reinsurers, financial institutions and insurance companies. NASA Earth observing satellite data is used to determine whether a client will receive a payout from a climatic event, such as drought or excess rainfall. This data is processed in real-time in order to allow objective, transparent and efficient payouts.

Resources

- Video: NASA Satellites Help Farmers in Central America's Dry Corridor

- Article: Building Climate Resilience with Satellite Data

- Written Interview with Iker Llabres

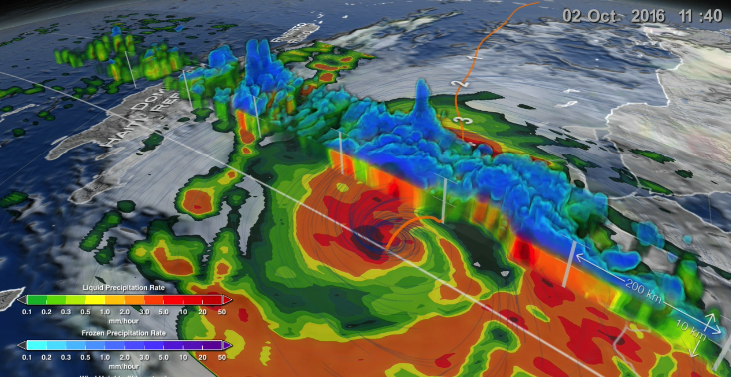

How NASA Data Helped During the 2020 Hurricane Season

The Atlantic "hurricane season" officially began on June 1 and runs through Nov. 30th. The Atlantic basin includes the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is predicting that we will have a busy hurricane season this year. Click here to find out why they are making this predication and where you can go to see the latest hurricane activity. Ever wonder why hurricanes have names? Visit this World Meteorological Organization (WMO) website to find out why they are named and see the names that are on board for this year's storms.

Predicting Earth's Climate with NASA Data

Climate change impacts all of us in various ways. Changes in soil moisture have a pronounced effect on agricultural production, which in turn impacts the food we grow to eat. Changes in precipitation patterns are leading to increases in drought in certain regions and causing flooding in others. All of these impacts are influenced by interactions among processes within the Earth system involving the atmosphere, ocean, land, ice, and life. These natural interactions combine with human influences, such as the release of greenhouse gases, and serve to drive the climate system, resulting in distinct regional variability of climates across the globe.

One way to address these issues and predict the impacts of climate change is using climate models - computer programs which simulate the complex interactions between Earth's systems. To help develop these climate models, scientists around the world rely on a wealth of data provided by NASA. Climate models support decision-making across communities spanning the humanitarian, public heath, energy, water, and agricultural sectors, enabling better crop forecasting, water resource management, and disaster management activities. These models can also address pressing questions such as what environments are likely to produce severe weather, how to prepare infrastructure to ensure climate resilience, and how our decisions today can affect how Earth's climate may change in the future.

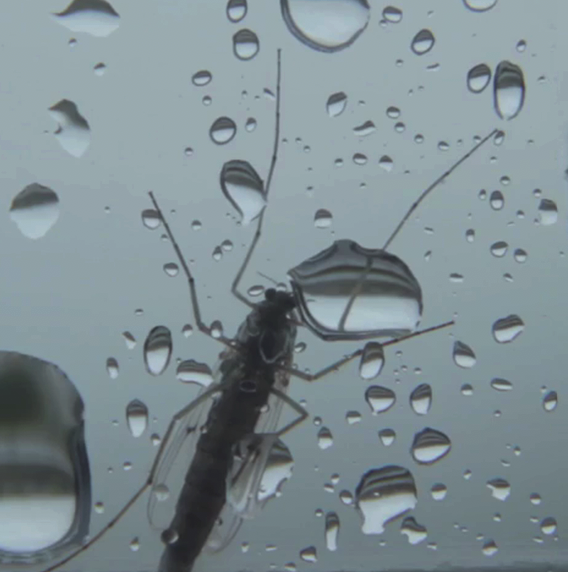

Using GPM and Other NASA Earth Data to Understand Vector-borne Disease

Have you ever been bitten by a mosquito or tick and worried that you might get sick as a result? Have you heard about zika, malaria, and dengue disease? In this webquest, you will learn how vectors- like mosquitoes and ticks- can indeed cause sickness and in some cases even death. You will explore some resources to learn more about these diseases and how you can help with efforts to reduce them. You might be surprised to learn that NASA’s Earth-observing satellites are helping people worldwide to predict and respond to vector-borne disease. Scientists and public health officials are working together to explore ways to use Earth-observing data sets to help predict, respond to, and better understand vector-borne diseases.

Helping Predict, Monitor, and Respond to Malaria

In the Amazon Rainforest, few animals are as dangerous to humans as mosquitos that transmit malaria. The tropical disease can bring on severe fever, headaches and chills and is particularly severe for children and the elderly and can cause complications for pregnant women. In rainforest-covered Peru the number of malaria cases has spiked such that, in the past five years, it has had on average the second highest rate in the South American continent. In 2014 and 2015 there were 65,000 reported cases in the country.

Containing malaria outbreaks is challenging because it is difficult to figure out where people are contracting the disease. As a result, resources such as insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor sprays are often deployed to areas where few people are getting infected, allowing the outbreak to grow.

To tackle this problem, university researchers have turned to data from NASA’s fleet of Earth-observing satellites, which are able to track the types of human and environmental events that typically precede an outbreak. With funding from NASA’s Applied Sciences Program, they are working in partnership with the Peruvian government to develop a system that uses satellite and other data to help forecast outbreaks at the household level months in advance and prevent outbreaks.

Helping Predict Outbreaks of Cholera

Prediction of an outbreak of diarrheal disease, like cholera, following a natural disaster remains a challenge, especially in regions lacking basic safe civil infrastructure to enable them easy access to clean freshwater resources. Cholera outbreaks are associated with disruption in the human access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene that results in the population using unsafe water containing pathogenic Vibrios. GPM data are being used to help scientists, government officials, and public health professionals predict where outbreaks of cholera may next arise in order to ensure clean freshwater resources are provided as well as be prepared to care for the sick.

Helping Track Zebra Migration

Botswana's Okavango Delta and the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans are two ends of a 360-mile round trip zebra migration, the second longest on Earth. In this animation, shades of red show dry areas, green represents vegetation, and the dots show GPS tracked zebras. The zebras begin at the Okavango Delta in late September. After the dry Southern hemisphere winter, November rains signal it is time to begin their two-week journey to the Salt Pans. The zebras feast on nutrient-rich grasses all summer and return to the Delta as the rain peters out in April.

Fences blocked this zebra migration from 1968 to 2004. After they came down, researchers began tracking zebras with GPS and discovered this migration. They compared the zebras' location to NASA satellite data of rainfall and vegetation, and they found that migrating zebras have quickly learned when to leave the Delta and the Salt Pans using environmental cues. Researchers then use these cues to predict when the zebras will be on the move, a powerful tool for conservation.