Building Connections: How NASA Data Empowers End Users, From Ecologists to Resource Analysts

So Much Data, So Little Time

NASA’s Earth-observing data are used daily in a wide variety of ways to improve life for humans and animals across the planet. Our climate is changing, and these changes are having a profound impact on communities and species in many ways. Changing extremes in precipitation and temperature are leading to a decline in species diversity, modification to ecosystems and animal habitats, as well as changing how some species interact with each other. To address this, many organizations are turning to the amazing yet complex wealth of Earth data, which can be used to successfully monitor many aspects of our environment.

With a wealth of data literally at their fingertips, it can be rather daunting for researchers and decision-makers to know which data to use for their purposes. Fortunately, there are organizations responding to this emerging need to help untangle the web of available data and make it more accessible and user-friendly. Bridging the gap between the data and end-users requires great communication skills as well as the ability to work with massive amounts of data and successfully translate the potential usability of these data. Data curators and data analysts are excited about the immense possibilities for the data from NASA’s Earth observing satellite missions.

Can you imagine how an ecologist studying the movement of animals might be interested in the impact of precipitation on animal migration? While ecologists have many tools to use in the field, having access to global datasets greatly enhances their ability to understand the factors involved in where and when animals migrate. Satellites from many countries collect and freely share their environmental data, which can be a huge benefit to improving life around the globe. One organization that uses data from the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission and other NASA Earth-observing satellites to better understand animal movement is Movebank.

Movebank provides a free online database that enables animal tracking researchers to manage, share, protect, analyze and store their data. The system includes a set of online tools that help ecologists link animal movement data with information from NASA and other Earth observing satellites, and view global environmental data, such as global precipitation and weather models. The project has over 20,000 users, and this number continues to grow as advances in technology allow the collection and analysis of increasingly high-resolution data. Having a wide range of data sets make it easier for ecologists to track animals and study their movement and distribution.

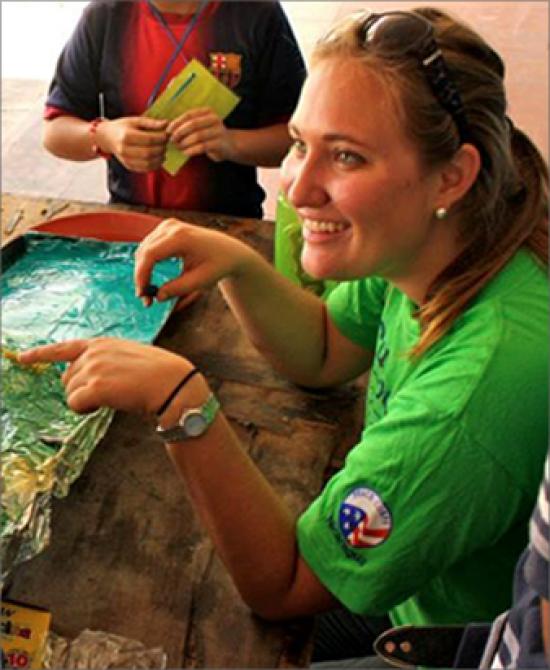

As one of Movebank’s data curators, Sarah Davidson is responsible for helping to design and test tools and provide support and training to help researchers make use of remote sensing data. Movebank works with many partners around the world and serves as a global archive for animal movement studies. One of the tools Sarah helped to develop that is frequently used by animal movement ecologists is the “Environmental Data Automated Track Association System” or Env-DATA

This system includes a set of free online tools which help ecologists link animal movement data with information from Earth observing satellites. Data from several NASA satellites are integrated into this system, including GPM precipitation data. Using the Env-DATA System enables ecologists to investigate the questions about how animal movement and migrations are impacted by the environment around them. Scientists around the world are better able to address new ecological questions and can combine datasets in order to test theories related to ecological patterns, evolutionary processes, and disease spread.

An example of the work being done by Movebank ecologists includes the research study “Tactical departures and strategic arrivals: Divergent effects of climate and weather on caribou spring migrations”. This research was led by Dr. Elie Gurarie at the University of Maryland, who investigated the impact of climate change on the spring migration patterns of caribou in the Arctic region. One of the things that Gurarie and her team were trying to better understand were the drivers of mass migrations of these caribou populations.

The authors analyzed movement data in specific regions of the Arctic for over 1,000 caribou collected over a time period ranging from 1995 to 2017. As they reviewed the departure and arrival times of these herds, they analyzed those variables against global climate indices and local weather patterns, such as rainfall. One of their findings was that the spring departure times seemed to be driven primarily by large-scale ocean driven phenomena, such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, when unique sea surface temperatures are recorded in the North Pacific Ocean. However, the arrival time appeared to depend much more on the weather conditions from the previous summer, rather than the actual time they departed. Being able to combine Earth data with data from the field, such as GPS collars on caribou, offers researchers an opportunity to more easily look for these potential cause and effect relationships.

World Resources Institute (WRI) is another organization that connects NASA Earth observations to the community of environmental decision makers. WRI is a global research organization that brings together over 60 countries from around the world to use data from many sources, including several NASA Earth observing missions, to generate ideas that are turned into actionable products and information systems for natural resource management. Several WRI projects use GPM precipitation data, including their Resource Watch platform. This dynamic online platform features hundreds of data sets that allow end-users to visualize data and develop potential solutions to challenges such as water insecurity, human migration, and state instability.

Liz Saccoccia is an early career research analyst who serves as the Resource Watch Data Team Lead. She works with the “Water, Peace and Security Partnership” which develops innovative tools and services to help stakeholders working in high-risk areas identify, understand and address water-related security risks. These risks occur due to the lack of freshwater resources to meet the needs of people’s daily lives. This water insecurity is growing around the world. Liz is currently working on improving the model to understand the role of water in these conflicts, in order to ultimately use water as a solution to increase human security.

When asked how she hopes to make a meaningful difference in this career, Liz responded:

“I want to focus on water issues, as I find this challenge essential to address. I believe that it will be easier to get people’s attention in the not-too-distant future regarding how important water security is to political stability. Already many large and small companies are making commitments and responding to this issue. WRI just published an update to our Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas last summer and it made the front page of New York Times! People are realizing that this is an important environmental issue. WRI presented at the United Nations’ Security Special session, to confirm along with multiple countries that water security is a national security risk.”

GPM data is an essential component of the data sets which are being ingested into the Resource Watch data dashboards. Having freshwater resources to meet the needs of farmers, as well as for meeting our daily needs, is essential to our lives. By tracking the most easily accessible freshwater, precipitation, GPM takes a lead in monitoring how much is falling all over the world.

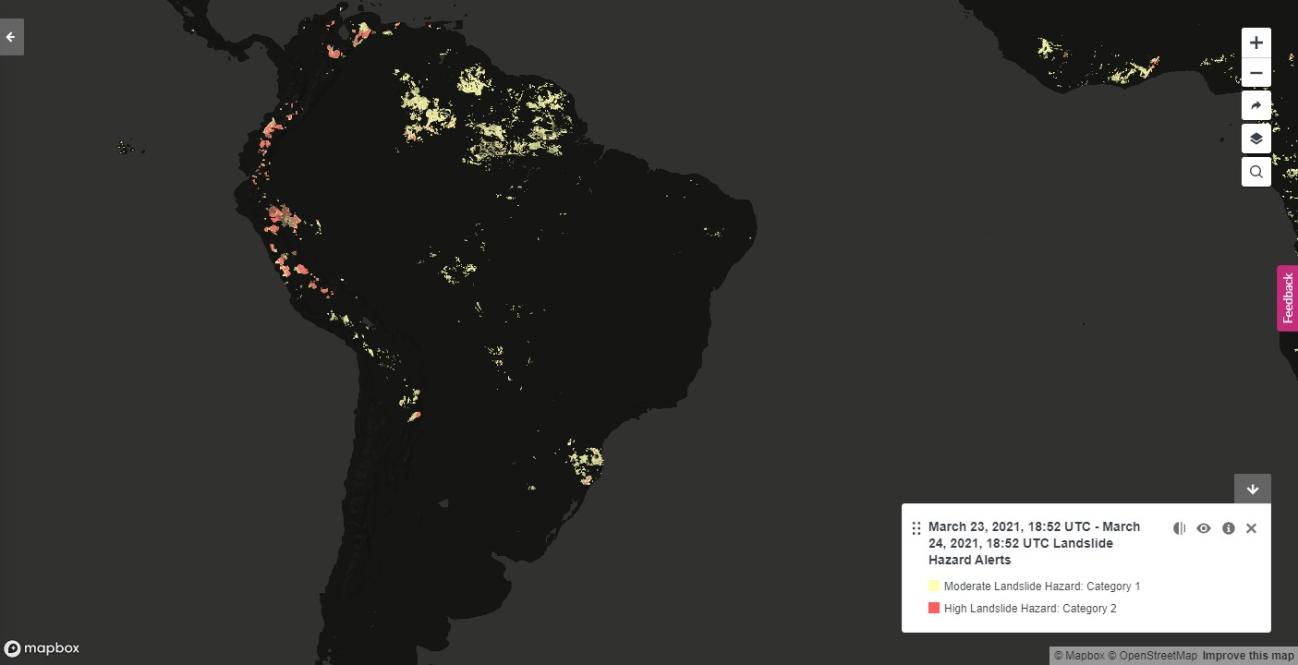

Landslides threaten people and infrastructure in many locations throughout the world. Resource Watch includes data on landslide susceptibility, based on factors such as slope, deforestation, infrastructure, and precipitation. They show end users how they can overlay landslide hazard alerts from NASA’s Landslide Hazard Assessment for Situational Awareness (LHASA) model to identify which regions are most susceptible to landslides in the next 24 hours. As precipitation is a common trigger of landslides, the LHASA Model uses GPM and TRMM data.

Landslide alerts for South America from World Resources Institute's Resourcewatch data portal. The data is derived from the NASA’s Landslide Hazard Assessment for Situational Awareness (LHASA) model. Credits: World Resources Institute

Building Connections to Serve the Planet

NASA’s Earth observing satellites supply an incredible reservoir of freely available data which can be used to support a huge variety of real-world applications. The need for these datasets has never been greater, and thus the importance of data curators and analysts such as Sarah and Liz is paramount. These early career scientists are analyzing and curating a wealth of freely available datasets and helping to bring these data to stakeholders around the world. Their ability to make complicated datasets accessible and meaningful to a wide variety of end-users is extremely important in ensuring that this data gets into the hands of those whose lives can be improved. They conduct training and write papers to ensure that others may benefit from their experience and knowledge. Through their work and the work of others, these complex data are being used by animal ecologists and decision-makers around the world to improve and protect all of us.

Learn More

- Explore more of the ways in which data from the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission are being used for ecological management.

- Learn more about Sarah Davidson and her work with Movebank

- Interview with Sarah Davidson

- Learn more about Liz Saccoccia and her work with World Resources Institute

- Interview with Liz Saccoccia