Help Create the Largest Landslide Database

This landslide occurred on June, 1, 2007 on a mountain near Canmore in Alberta, Canada. The Flickr photo was taken by Sheri Teris (Creative Commons)

This landslide occurred on June, 1, 2007 on a mountain near Canmore in Alberta, Canada. The Flickr photo was taken by Sheri Teris (Creative Commons)Landslides cause thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in property damage each year. Surprisingly, very few centralized global landslide databases exist, especially those that are publicly available.

Now NASA scientists are working to fill the gap—and they want your help collecting information. In March 2018, NASA scientist Dalia Kirschbaum and several colleagues launched a citizen science project that will make it possible to report landslides you have witnessed, heard about in the news, or found on an online database. All you need to do is log into the Landslide Reporter portal and report the time, location, and date of the landslide—as well as your source of information. You are also encouraged to submit additional details, such as the size of the landslide and what triggered it. And if you have photos, you can upload them.

Kirschbaum’s team will review each entry and submit credible reports to the Cooperative Open Online Landslide Repository (COOLR) — which they hope will eventually be the largest global online landslide catalog available.

Landslide Reporter is designed to improve the quantity and quality of data in COOLR. Currently, COOLR contains NASA’s Global Landslide Catalog, which includes more than 11,000 reports on landslides, debris flows, and rock avalanches. Since the current catalog is based mainly on information from English language news reports and journalists tend to cover only large and deadly landslides in densely populated areas, many landslides never make it into the database. Landslide Reporter should help change this because it makes it possible for people to submit reports, including first-hand accounts, from anywhere in the world.

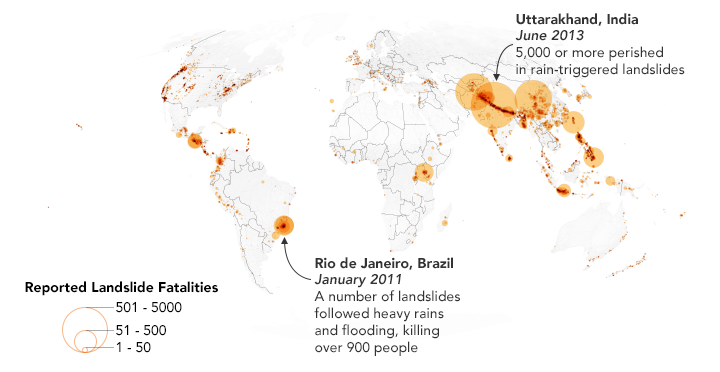

This map shows 2,085 landslides with fatalities as reported in the Global Landslide Catalog, which is currently included in the Cooperative Open Online Landslide Repository (COOLR). NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using landslide susceptibility data provided by Thomas Stanley and Dalia Kirschbaum (NASA/GSFC).

This map shows 2,085 landslides with fatalities as reported in the Global Landslide Catalog, which is currently included in the Cooperative Open Online Landslide Repository (COOLR). NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using landslide susceptibility data provided by Thomas Stanley and Dalia Kirschbaum (NASA/GSFC).Kirschbaum plans to use this database to improve the algorithm for her team’s landslide prediction model. The model, known as the Landslide Hazard Assessment for Situational Awareness (LHASA) model, analyzes rainfall and land characteristics in an area that might make a landslide more susceptible. The model produces forecasts of potential landslide activity every 30 minutes. In some cases, however, the model predicts more or less potential activity.

“With more ground data to validate the model, we can create a better tool for improving situational awareness and research for this pervasive hazard. We could better anticipate and forecast where landslides may impact populations,” said Kirschbaum.

Check out posts by Caroline Juang on Discover magazine’s citizen science blog and by David Petley on American Geophysical Union’s Landslide Blog to find out more. You can also follow the project on Twitter (@LandslideReport) and Facebook.