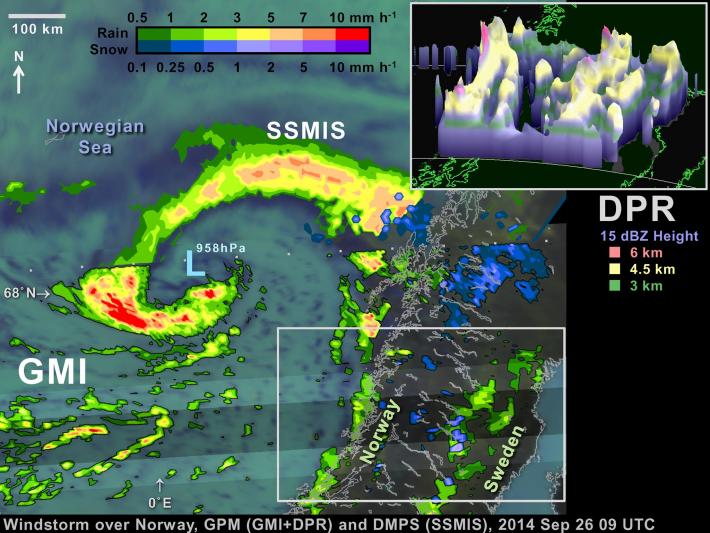

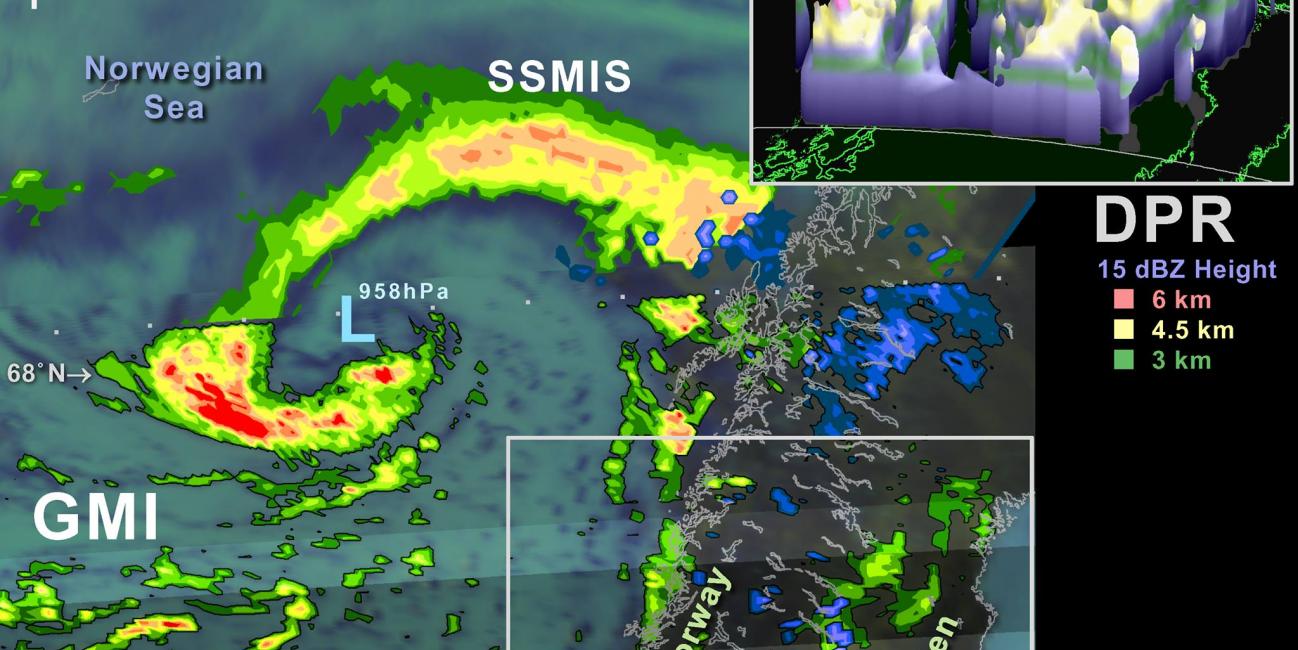

GPM Satellite Sees a Windstorm over Norway

On September 26, the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) satellite flew over an extra-tropical cyclone whose center was approaching Norway. The Norwegian weather service reported that this storm brought gale-force winds to parts of Norway's coast and mountains (20 m/s in the mountains and 50 m/s just off-coast, late at night on September 26).

Extra-tropical cyclones this strong or stronger are a regular feature of northern European winters. The particularly damaging ones are called "windstorms." Borrowing a page from hurricane forecasters, some weather agencies in affected countries name these storms. In fact, one such naming system called the September 26 extra-tropical cyclone "Irina" (Learn more from the Institute for Meteorology at the Free University of Berlin:http://www.met.fu-berlin.de/adopt-a-vortex/tief/).

The GPM satellite will help scientists study these fast moving, rapidly evolving, and sometimes costly cyclones. The GPM satellite carries both a dual-frequency precipitation radar (the DPR) and the latest passive-microwave radiometer (the GPM Microwave Imager, GMI).

While this extra-tropical cyclone was definitely not a hurricane, it had some hurricane-like characteristics. A number of scientists have shown that some of these cyclones actually draw a considerable fraction of their energy from the same source as hurricanes: heat from the ocean surface forming a "warm core" at the center of the storm (Hart 1983, Monthly Weather Review). A warm core is the heat engine of a hurricane; the warm core the system of wind and pressure that enables a hurricane to reach such damaging wind speeds. In contrast, conventional wisdom has it that large storm-systems outside the tropics are "cold core", which means that they draw their energy primarily from baroclinic instability, which is the energy of weather fronts.

In particular, this extra-tropical cyclone on September 26 appeared to have some hurricane-like characteristics. For one thing, the automated realtime analysis performed at Florida State University found evidence of a "warm core" functioning within this extra-tropical cyclone (Learn more: http://moe.met.fsu.edu/cyclonephase). This automated analysis is food for thought, not the final word on this cyclone. Independent of the FSU analysis, the GPM Microwave Imager (GMI) saw an arc of strong precipitation nearly ringing the low-pressure center of the cyclone, reminiscent of a hurricane's eyewall. The cyclone's center itself achieved an impressively low surface pressure for an extra-tropical storm: under 960 hPa according to realtime analysis by NOAA's Ocean Prediction Center (http://www.opc.ncep.noaa.gov/).

Somewhat like a tropical storm, GMI and a similar instrument on a DMSP satellite saw that this cyclone had a spiral band of convective precipitation that extended out from the inner arc of precipitation.

This rainband extended north, then east, then southeast where the rainband was associated with an eastward moving cold front. According to the Norwegian weather service, this cold front was already affecting the coast of Norway at the time of the GPM satellite overflight (Learn more: http://www.yr.no/nyheter/1.11953411, 2014 Sep 26 1UTC).

The GPM Microwave Imager observations suggested that coastal Norway and low-lying parts of Sweden were experiencing light rainfall, while the mountains separating the two countries were experiencing scattering snow showers. In contrast, the data from the GPM Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR) suggests that the rain and snow may have been more widespread. Complex, mountainous terrain, such as this, can make it difficult for passive instruments, such as GMI, to estimate rainfall, while the radar signal from rain or snow a few kilometers above the earth's surface can be reliably observed by the GPM satellite's radar.

The GPM mission includes not only the satellite that collected these observations but also data analysis and data processing efforts. These efforts will calibrate and knit together the passive microwave instruments flying on multiple satellites, using information gathered from GMI and DPR. The usefulness of having precipitation estimates from all satellite at your fingertips is illustrated by this extra-tropical cyclone. GPM's Precipitation Processing System (PPS) at NASA Goddard not only generated realtime estimates of precipitation from the GPM satellite's instruments but also instruments such as SSMIS on the DMSP satellites. It was a SSMIS instrument that captured the precipitation along the northern arc of this cyclone, which was useful since the higher-resolution GMI instrument did not collect observations from that part of the storm.

GPM data provided by NASA and JAXA. For more information about

GPM, please visit http://pmm.nasa.gov/gpm