What is the difference between a tornado and a hurricane?

Both tornadoes and hurricanes are characterized by extremely strong horizontal winds that swirl around their center and by a ring of strong upward motion surrounding downward motion in their center. In both tornadoes and hurricanes, the tangential wind speed far exceeds the speed of radial inflow or of vertical motion.

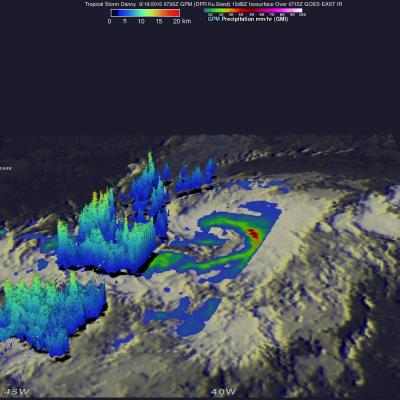

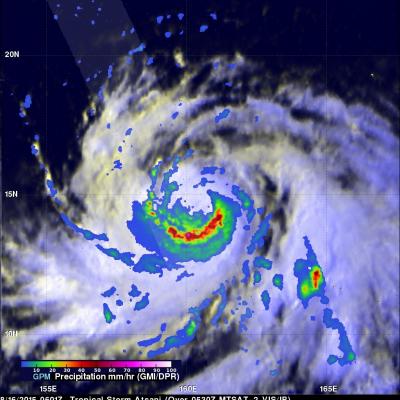

Hurricanes always and tornadoes usually rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the southern hemisphere. The Earth's rotation determines this direction for the storms' rotation in each hemisphere. Local winds are sometimes able to cause a tornado to form that spins in the opposite direction from the typical direction for that hemisphere.

The most obvious difference between a tornado and hurricane is that a hurricane's horizontal scale is about a thousand times larger than a tornado. In addition, hurricanes and tornadoes form under different circumstances and have different impacts on the atmosphere.

Tornadoes are small-scale circulations, that are rarely more than a few hundred feet across when they touch the ground. Most tornadoes grow out of severe thunderstorms that develop in the high wind-shear environment of the United States Central Plains during spring and early summer. Many tornadoes form when the large-scale wind flow leads to a violent clash between moist, warm air traveling north from the Gulf of Mexico and cold, dry, continental air coming from the United States Northwest. Tornadoes can also form in many other locations and from other forcing factors. For example, a hurricane making landfall may trigger many tornadoes to form.

Tornado wind speeds may reach 100 to 300 mph and cause havoc on the ground, but tornadoes typically last only a few minutes and rarely travel more than 10 or 20 miles along the ground. Tornadoes have little impact on storms that spawn them or collectively on the global circulation of the atmosphere.

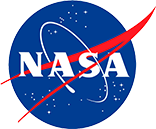

Hurricanes, on the other hand, are large-scale circulations that are 60 to over 1,000 miles across. Hurricanes form near the Equator, generally between 5 and 20 degrees latitude, but never right on the Equator. Hurricanes always form over the warm waters of the tropical oceans and generally where the sea-surface temperature exceeds 26.5°C (76°F).

A hurricane may travel thousands of miles and persist over several days or weeks. During its lifetime, a hurricane will transport a significant amount of heat up from the ocean surface and into the upper troposphere or even lower stratosphere. Even though hurricanes form only sporadically, they do affect the global atmosphere's circulation in measurable ways, although this is still an active area of research.