Using GPM Data for Weather, Climate, and Land Surface Modeling

Using GPM Data for Weather, Climate, and Land Surface Modeling

Variations in rain, snow, and other forms of precipitation are an integral part in everyday weather and long term climate trends. Initialization of short-term weather and long-term climate models with accurate precipitation information enhances their prediction skills and extends their skillful lead times. To get the resolution and temporal coverage to measure precipitation across the globe, we often rely on satellite information. Satellite data can play a fundamental role in our ability to monitor and predict weather systems as well as to forecast future changes to our climate and land surface. Satellite data from GPM’s suite of precipitation products are integrated into numerical weather prediction models that are operated by operational partners to provide and improve the observations from which the forecasts are then generated. Similarly, climate and land surface models use satellite precipitation observations from GPM to describe the conditions that exist today in order to project how conditions may change in the future. The Weather, Climate, and Land Surface Modeling applications area promotes the use of GPM data to help monitor existing weather activity and model future behavior of precipitation patterns and climate.

Overview

Variations in rain, snow, and other forms of precipitation are an integral part in everyday weather and long term climate trends. Initialization of short-term weather and long-term climate models with accurate precipitation information enhances their prediction skills and extends their skillful lead times. To get the resolution and temporal coverage to measure precipitation across the globe, we often rely on satellite information. Satellite data can play a fundamental role in our ability to monitor and predict weather systems as well as to forecast future changes to our climate and land surface. Satellite data from GPM’s suite of precipitation products are integrated into numerical weather prediction models that are operated by operational partners to provide and improve the observations from which the forecasts are then generated. Similarly, climate and land surface models use satellite precipitation observations from GPM to describe the conditions that exist today in order to project how conditions may change in the future. The Weather, Climate, and Land Surface Modeling applications area promotes the use of GPM data to help monitor existing weather activity and model future behavior of precipitation patterns and climate.

GPM Data for Decision Making

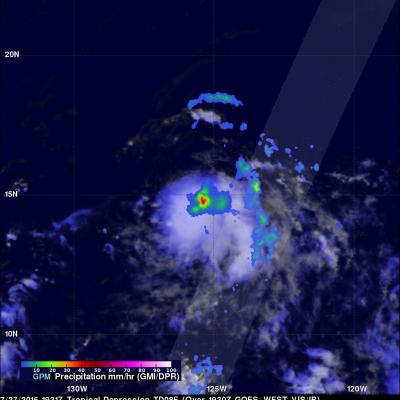

Numerical weather prediction (NWP) is the use of computer models to predict upcoming weather. Specifically, NWP centers rely on microwave-based satellite rainfall information, such as data retrieved from GPM’s GMI, to improve short- to long-term weather forecasts and correct track forecasts for tropical cyclones. In addition, NWP centers create precipitation products for “nowcasting” weather in the immediate 1-5 hours (e.g. using near-real-time rainfall data from GPM) to meet the needs of a wider user community, including weather forecasters, hydrologists, farmers, numerical modelers, the military and the climate community. Methods for integrating rainfall data are constantly evolving and advancing, and with GPM’s advanced instruments, scientists can influence and enhance their scientific research and benefit socioeconomic activities.

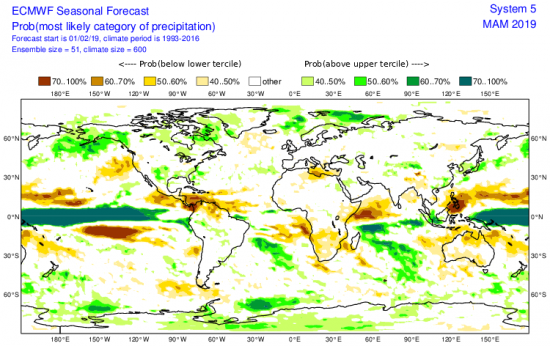

To understand the changing climate and make future climate predictions, scientists need to use sophisticated computer models to recreate Earth’s climate conditions. Understanding current rainfall and snowfall variability, among other climate factors on regional and global scales, helps scientists model future behavior of precipitation patterns and climate. But for a system as complicated as the Earth, the models are only as good as the data provided. Satellite precipitation measurements from GPM and its predecessor TRMM provide global scale observational data sets that are comprehensive and consistent over long time periods, two characteristics scientists need to understand the relationships between different parts of the climate system. Specifically, organizations use GPM and TRMM data as input to verify and validate their seasonal and climate model simulations. The ultimate goal is to be able to predict changes in climate on time scales as short as the next hurricane season and as far into the future as changes that may occur in the coming decades or centuries.

Precipitation is the fundamental driver of land surface hydrological processes and a key component of the terrestrial water cycle, which in turn affects the functioning of atmospheric and climate processes. High-resolution modeling of land surface hydrological processes requires detailed rainfall estimates as inputs to improve understanding of the state of the water cycle and impacts on land-surface processes during extreme events. Satellite precipitation data from GPM is integrated into land surface models to study surface features and how they change due to manmade and natural conditions such as urbanization and erosion. The use of GPM precipitation data together with other satellite data including soil moisture within land surface models will improve weather and hydrological prediction, which will help city planners and even decision makers save lives.

Weather & Climate Featured Resources

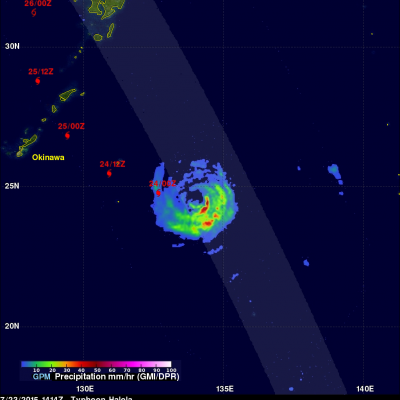

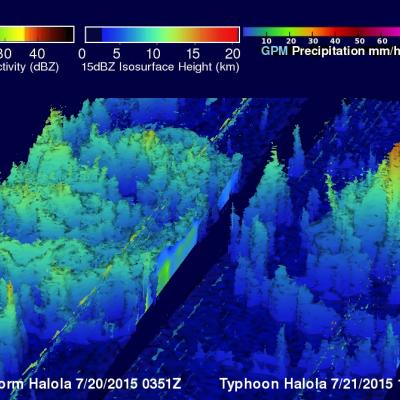

Typhoon Halola Threatening Japan

GPM Sees Halola Becoming A Typhoon

IMERG Measures Record Rainfall From Hurricane Delores Remnants

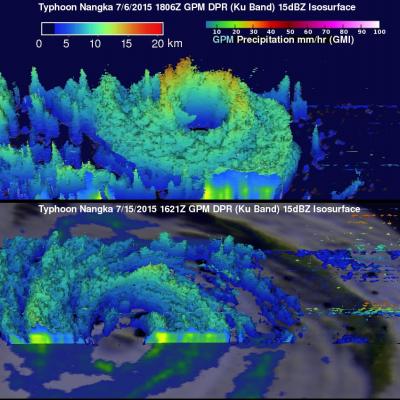

Weaker Typhoon Nangka Threatens Japan

Through rain and snow, hurricane, typhoon and monsoon, flash flood and bomb cyclone, for ten years, the joint NASA-JAXA Global Precipitation Measurement mission has measured a lot of water. GPM’s Core Observatory satellite launched from Tanegashima Space Center in Japan in early 2014, becoming the first satellite to be able to see through the clouds and measure liquid and frozen precipitation from the Equator to polar regions using a radar. Now in its tenth year of operation, we look at ten events brought to light by this groundbreaking mission. Credits: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

The most detailed view of our daily weather has been created using NASA's newest extended precipitation record known as the Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM, or IMERG analysis. The IMERG analysis combines almost 20 years of rain and snow data from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) and the joint NASA-JAXA Global Precipitation Measurement mission (GPM). The daily cycle of weather, also known as the diurnal cycle, shapes how and when our weather develops and is fundamental to regulating our climate.

Music Credits: "Battle For Our Future" and "Wonderful Orbit" by Tom...

NASA engineer Manuel Vega can see one of the Olympic ski jump towers from the rooftop of the South Korean weather office where he is stationed. Vega is not watching skiers take flight, preparing for the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics and Paralympic games. Instead, he’s inspecting the SUV-sized radar beside him. The instrument is one 11 NASA instruments specially transported to the Olympics to measure the quantity and type of snow falling on the slopes, tracks and halfpipes. NASA will make these observations as one of 20 agencies from eleven countries in the Republic of Korea as participants...

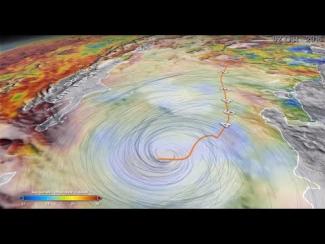

NASA researchers now can use a combination of satellite observations to re-create multi-dimensional pictures of hurricanes and other major storms in order to study complex atmospheric interactions. In this video, they applied those techniques to Hurricane Matthew. When it occurred in the fall of 2016, Matthew was the first Category 5 Atlantic hurricane in almost ten years. Its torrential rains and winds caused significant damage and loss of life as it coursed through the Caribbean and up along the southern U.S. coast.

Music: "Buoys," Donn Wilkerson, Killer Tracks; "Late Night Drive," Donn...

NASA scientists can measure the size and shape distribution of snow particles, layer by layer, in a storm. The Global Precipitation Measurement mission is an international satellite project that provides next-generation observations of rain and snow worldwide every three hours.

- GPM Weather Applications One-pager (pdf)

- NOAA National Weather Service (NWS)

- Precipitation Education: Weather & Climate

- NASA IMPACTS Campaign (Investigation of Microphysics and Precipitation for Atlantic Coast-Threatening Snowstorms)