Using GPM Data for Disasters and Risk Management

Too much or too little rainfall can have significant impacts on populations around the world. As population and global temperatures increase, it is crucial to understand what locations will become more vulnerable to extreme rainfall and drought and the subsequent natural hazards (e.g., landslides) and risks (e.g., lose of property) they impose. Satellites allow us to monitor changes in the precipitation, especially over oceans and regions where ground-based data are sparse. With its near-real-time precipitation estimates and near global coverage, GPM serves as an essential tool for assessing risk and planning disaster response and recovery. For example, near-real-time precipitation data from GPM are used within various models to help monitor and predict the path and intensity of tropical storms, vegetation fire starting and spreading, and landslide activity across the globe. The Disasters and Risk Management applications area seeks to use the GPM precipitation satellite data to improve forecasting, preparation, response, recovery, mitigation and insurance of natural hazards including tropical cyclones, floods, droughts, wildfires, landslides, and other extreme weather events.

Overview

Too much or too little rainfall can have significant impacts on populations around the world. As population and global temperatures increase, it is crucial to understand what locations will become more vulnerable to extreme rainfall and drought and the subsequent natural hazards (e.g., landslides) and risks (e.g., lose of property) they impose. Satellites allow us to monitor changes in the precipitation, especially over oceans and regions where ground-based data are sparse. With its near-real-time precipitation estimates and near global coverage, GPM serves as an essential tool for assessing risk and planning disaster response and recovery. For example, near-real-time precipitation data from GPM are used within various models to help monitor and predict the path and intensity of tropical storms, vegetation fire starting and spreading, and landslide activity across the globe. The Disasters and Risk Management applications area seeks to use the GPM precipitation satellite data to improve forecasting, preparation, response, recovery, mitigation and insurance of natural hazards including tropical cyclones, floods, droughts, wildfires, landslides, and other extreme weather events.

GPM Data for Decision Making

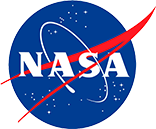

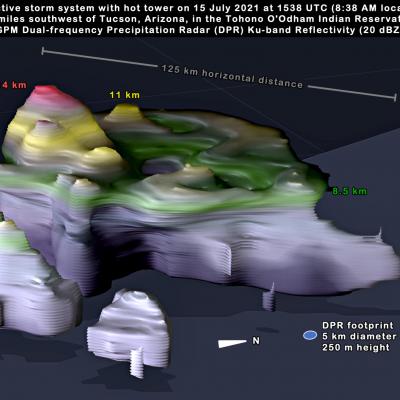

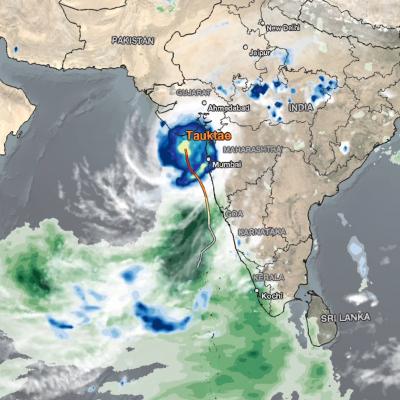

The GPM Mission provides insight into how and why some tropical cyclones intensify and others weaken as they move from tropical to mid-latitude systems. The GPM Core Observatory’s GMI and DPR instruments allow scientists to study the internal structure of storms throughout their life cycle, and view how they change over time. Specifically, the GMI has the capability to measure the amount, size, intensity, and type of precipitation, from heavy-to moderate rain to light rain and snowfall. The DPR returns three-dimensional profiles and intensities of liquid and solid precipitation, revealing the internal structure of storms within and below clouds. Scientists use these instruments to track tropical cyclones and forecast their progression and to verify their tropical cyclone computer models. They also use instrument data to understand the distribution and movement of latent heat throughout the storm, particularly in the development of hot towers in the wall of clouds around the eye, which have been linked to rapid intensification. Together, these instruments will improve hurricane tracking and forecasts, which can help decision makers save lives.

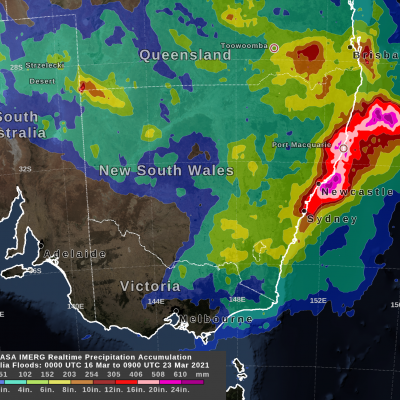

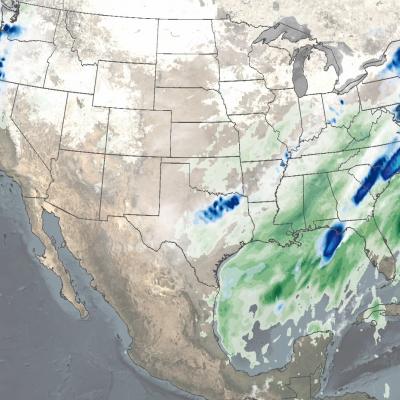

To better understand and predict floods scientists have developed hydrological models based on how much rainfall occurs and where the water will likely go once it hits the ground. They use several satellite precipitation datasets within these models to provide near real-time estimates of when and where areas may flood on local, regional, and global scales. GPM provides frequent precipitation observations with near global coverage, of which 80% are less than 3 hours apart, exceeding the minimum deemed necessary for hydrometeorological applications. Therefore, rainfall data measured by the GPM Mission and its products, like the Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) data product, helps us better understand how changing precipitation patterns at multiple scales translates changes into hydrologic fluxes and states that can be used for flood detection and warning systems.

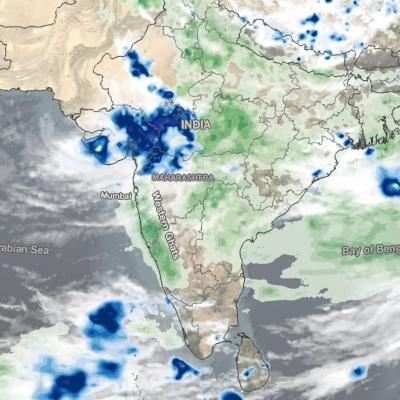

Landslides are one of the most pervasive hazards in the world, resulting in more fatalities and economic damage than is generally recognized. Saturating the soil on vulnerable slopes, intense and prolonged rainfall is the most frequent landslide trigger, but seismicity, river undercutting, freeze-thaw processes, and human activity can also cause extensive and devastating landslides. Understanding where and when landslides have occurred in the past and where they may occur in the future is extremely challenging because of the lack of ground-based sensors at the landslide site to provide both triggering information (e.g. rainfall intensity and duration), and the timing and extent of the mass movement events. Precipitation measurements from remote sensing allows us to gain new insight to identify landslide activity, characterize the triggering patterns of these events spatially and temporally, assess the surface conditions for potential activity, and support the full cycle of disaster risk assessment. In particular, GPM’s more frequent and more detailed coverage of precipitation across the globe can help improve landslide model accuracy and expand potential landslide forecasting capabilities.

Wildfires play an integral role in maintaining ecosystem biodiversity and structure. Wildfires, which include any non-structure fire that occurs in vegetation or natural fuels, is an essential process that connects terrestrial systems to the atmosphere and climate. However, the effects of fire can be disastrous, both immediately (e.g., poor air quality, loss of life and property) and through post-fire impacts (floods, debris flows/landslides, poor water quality). Wildfires can be triggered by several factors including lightning, high winds, drought, and people.

There are several ongoing activities using remote sensing data to support pre-, active- and post-fire research, as well as the applicable use of these data and products in support of management decisions and strategies, policy planning and in setting rules and regulations. Frequent precipitation measurements from GPM along with temperature and land cover measurements from other satellites can provide key information to determine the overall dryness of an area and the potential start and spread of a vegetation fire.

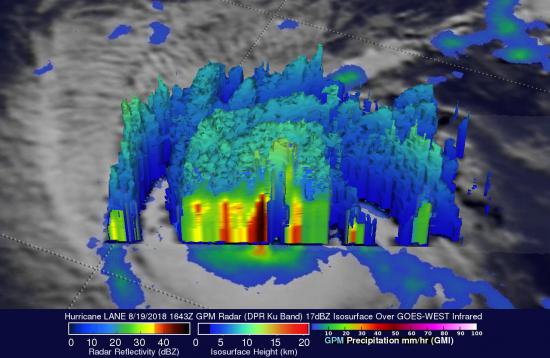

Many regions in the world experience severe weather such as thunderstorms, hail, tornadoes, and blizzards every year. Severe weather usually comes with heavy precipitation and causes unexpected hydrometeorological hazards, such as floods or landslides, which can affect thousands of people, posing a threat on life and property. Therefore, it is critically important to monitor severe weather and estimate heavy precipitation so that the occurrence and intensity of associated hydrometeorological hazards can be well identified, detected, and forecasted. Where ground-based instruments are sparse, remote sensing systems can be especially useful to observe and monitor these extreme events. Microwave sensors used by the GPM Mission allows scientists to map thunderstorm cores to gain insight into storm structures and mesoscale dynamics (e.g. thunderstorms to hurricanes) as well as detect light rain to moderate-to heavy rain and snowfall. Delivery of precipitation data from the GPM Mission is crucial for operational and research organizations to advance precipitation measurement science to improve weather forecasting that can subsequently benefit society for years to come.

Every year, landslides wipe out roads or town, devastating floods put city blocks underwater, or a violent hurricane devastates the coastal communities. Natural hazards, like Hurricane Maria or flooding in Houston, have huge impacts on people around the world. Heavy rains and large storm systems are often significant factors that cause these disasters to have huge economic costs or even kill people. The best defense against natural hazards is accurate and early warning systems. Understanding the timing, location, and intensity of precipitation extremes using GPM data, organizations that handle disaster response and recovery can monitor, assess, and understand the damage or potential damage of a disaster. These efforts help to minimize the impact of a natural disaster as well as effectively coordinate with organizations and the public before, during, after so as many people are safe and needs are met.

The insurance and disaster management industries are closely related; dealing with the risk of natural disaster and managing the events following disasters. Reinsurance companies work to understand the need of its potential customers and the risks to which they may be exposed. A companies’ success is generally tied to the ability to forecast the probability of natural hazards, including storms, floods, and landslides. Earth Science data and information derived from remote sensing instruments over the last decade have made it more feasible to develop climate records and understand region’s susceptibility to a natural disaster. Such data are then used to design payout triggers when natural hazards occurs. Policyholders are then compensated according to the strength of the measured event against those triggers. Specially, reinsurance companies across the world use rainfall data from GPM to develop rainfall thresholds to design insurance payouts when disasters strike.

Disasters Featured Resources

Through rain and snow, hurricane, typhoon and monsoon, flash flood and bomb cyclone, for ten years, the joint NASA-JAXA Global Precipitation Measurement mission has measured a lot of water. GPM’s Core Observatory satellite launched from Tanegashima Space Center in Japan in early 2014, becoming the first satellite to be able to see through the clouds and measure liquid and frozen precipitation from the Equator to polar regions using a radar. Now in its tenth year of operation, we look at ten events brought to light by this groundbreaking mission. Credits: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

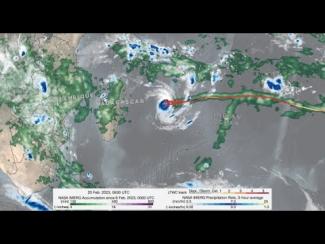

GPM IMERG precipitation rates and totals from Tropical Cyclone Freddy, Feb. 6 - March 12, 2023. Credit: NASA

Download in high resolution from the NASA Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio

Cameras outside the International Space Station captured dramatic views of Hurricane Zeta at 12:50 pm ET October 28, as it churned 200 miles south-southwest of New Orleans packing winds of 90 miles an hour. Credit: NASA International Space Station

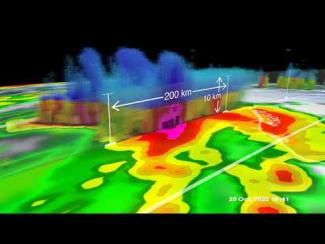

GPM overpass of Tropical Storm Zeta on October 25 at approximately 2:15pm CDT (19:15 UTC). Half-hourly rainfall estimates from NASA’s multi-satellite IMERG dataset are shown in 2D on the ground, while rainfall rates from GPM’s DPR instrument are shown as a 3D point cloud, with liquid precipitation shown in green, yellow and red, and frozen precipitation shown in blue and purple. Credit: NASA Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio

View an interactive 3D visualization of this overpass in STORM Event Viewer

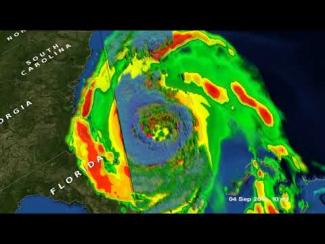

GPM captured Dorian at 10:41 UTC (6:41 am EDT) on the 4th of September when the storm was moving north-northwest parallel to the coast of Florida about 90 miles due east of Daytona Beach. Three days earlier, Dorian had struck the northern Bahamas as one of the most powerful Category 5 hurricanes on record in the Atlantic with sustained winds of 185 mph. The powerful storm to ravaged the northern Bahamas for 2 full days. During this time, Dorian began to weaken due to its interactions with the islands as well as the upwelling of cooler ocean waters from having remained in the same location...